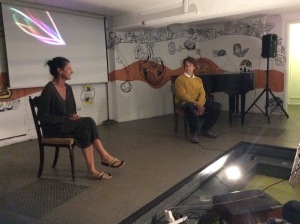

Last night was an event at our local community cafe, the Hill Station, where there was a screening and discussion about the first steps in a public art project led by Artmongers and Bold Vision, aiming at a ‘cultural twinning’ of our community with a Syrian refugee camp in Azraq in Jordan. Bold Vision is the charity at the heart of our community in SE14 (Telegraph Hill/New Cross Gate) that helps give agency to people, for example to run the library closed by the council, to build a community cafe, to carve common gardens out of scrappy land and so on. Incidentally, see the Underhillians mural in this photo – which I’ve created with other local artists and ideas of many children. This is an example of how Bold Vision’s spaces are enlivened by creativity. It aims to build creative skills, agency and social cohesion. And Artmongers is a local art business run by Patricio Forrester, who helped set up Bold Vision.

Last night was an event at our local community cafe, the Hill Station, where there was a screening and discussion about the first steps in a public art project led by Artmongers and Bold Vision, aiming at a ‘cultural twinning’ of our community with a Syrian refugee camp in Azraq in Jordan. Bold Vision is the charity at the heart of our community in SE14 (Telegraph Hill/New Cross Gate) that helps give agency to people, for example to run the library closed by the council, to build a community cafe, to carve common gardens out of scrappy land and so on. Incidentally, see the Underhillians mural in this photo – which I’ve created with other local artists and ideas of many children. This is an example of how Bold Vision’s spaces are enlivened by creativity. It aims to build creative skills, agency and social cohesion. And Artmongers is a local art business run by Patricio Forrester, who helped set up Bold Vision.

What if you took some of this artistic approach, with a big dose of goodwill from our locality, to a Syrian refugee camp?

Patricio and Catherine showed a short documentary film of their artmaking activities in Azraq for 8 days this summer, then we had a discussion about its impacts and what we could build on. They plan to return in March, and also there are many things we can do here, to connect with the camp.

Patricio had the idea 2 years ago and it came about through Catherine’s link with the charity, Care International, who provided support with the journey and accommodation. They couldn’t go into Syria, as it’s too dangerous.

Catherine set the scene: Imagine having 15 million refugees coming to your country. That proportionally is Jordan taking refugees from Syria. The population of Azrac camp is 20,000 and growing, and has three different ‘towns’.

When Catherine and Patricio arrived, it felt tougher than they had expected to know where to begin. There was no precedent in the camp, or in the previous work of Artmongers. It was hard for them to understand what it was like for the refugees, to have fled in the night, to cross the border, to not know how to live. They found the whole camp so quiet, no radios, no chatter, just people inside their shelters wondering what to do next. The boredom is crushing. There is no sense of when they might have something meaningful to do again.

Patricio was affected by the silence and for a while couldn’t talk. (Later, when he got to a paint shop he felt himself and could talk at last! That says a lot about the experience of being in limbo – that people come alive and be themselves when they are with tools they know how to use and have a purpose to use them – and conversely die inside without it.)

Catherine began the process by going into homes with a questionnaire. This was based on the RSA’s Social Mirrorresearch which had been piloted in New Cross Gate. It used the NEF Five Measures of Wellbeing, and asked questions about their social connections, activities and needs.

One question was: how many people outside the family did you speak to yesterday? For women the answer was invariably ‘none’, as they are expected to stay indoors. Also, the people don’t have skills and confidence to make friends because they had grown up in traditional villages where you don’t have to continually forge a community.

The strong theme in their responses was: we want colour! So, they went to buy paint.

They began by training some helpers. These people had doubts on the first day but then on the second day they all turned up willing and confident for their training. They were fully ready to embark on something that would help improve their camp.

The first activity was called Peace Rocks. They worked with materials they could find, which was rocks on the ground. Children (and adults) picked one, tied string round it, dipped it in paint of different colours, then a bit of glitter, then tied it to a fence. Patricio first tried to insist they only used one colour each, but the children had a better idea – to double or triple dip – leading to a much more marbled result. Some people found the experience so exciting and joyful, such a simple act of mixing colours and making something in your own way.

It had a lot of subversive symbolic power too. The people are very worried about further uprising and insecurity in their lives, so there are fears around the idea of picking rocks off the ground which could be thrown. The colonel in charge said “you are decorating weapons”, so in response they decided to call them ‘peace rocks’. A rock is a weapon until you paint it. The other symbolic dimension was that people felt stuck in the floor like the rocks on ground so lifting them up to transform them with colour felt like a transformation of self.

The next morning, unexpectedly, all the rocks had gone. Everyone had taken them home. Apparently, the instinct in the camp is to focus on your home, to protect your family, to take and keep things there and personalise your home. Things like communally planted trees or artificial turf had all disappeared. While some homes have nothing but a mat on floor and a UN aid box (refusing to accept they have to make a home), others use found materials to make ornaments and to delineate spaces. The head of Care International explained that the people do not come from the same community. Syria is not one homogenous place. Also, because the people are not in a position to create a thriving self-managed and sustainable city in their camp, a sense of community is not built over night.

The next morning, unexpectedly, all the rocks had gone. Everyone had taken them home. Apparently, the instinct in the camp is to focus on your home, to protect your family, to take and keep things there and personalise your home. Things like communally planted trees or artificial turf had all disappeared. While some homes have nothing but a mat on floor and a UN aid box (refusing to accept they have to make a home), others use found materials to make ornaments and to delineate spaces. The head of Care International explained that the people do not come from the same community. Syria is not one homogenous place. Also, because the people are not in a position to create a thriving self-managed and sustainable city in their camp, a sense of community is not built over night.

After the Peace Rocks activity, they decided to create a shared public space where people might want to meet, to stimulate a sense of community. Catherine was struck that there were no benches where people sat to chat. There was a mosque built from shelters but it was used only by men. Any place of value such as a school or computer building is fenced off, so there are very few shared places without barbed wire. So they created Hope Square, by painting large diamond shapes of different colours on the buildings. Hope Square was the first place in the camp to have a name.

After working all day during Ramadan in 46 degree heat, totally sweaty and exhausted, Patricio was lifted up to hear one participant say “They let us see the rainbow again”. Another said that “the colour makes it more comfortable to the eye”. The people were left with supplies of paint and brushes so they could do what they wanted with it, and continue the work. It really did give a sense of agency, as normally the supplies they are given are just to help them survive (gas, water, food) and they feel they are treated as children. With creative materials, they can make decisions, and it may lead to more empowerment. For example, they may start to give names to more places or to exchange their skills. Because the place is so bureaucratic, militarised and controlled, people tend towards being passive. The hope is that if you give people paint and wake them up to creative possibility, it can inspire further ways of creating, learning and sharing.

So, what next? Did this, as action-research, generate ideas for more ways of supporting them?

Some ideas that came from the camp included the ‘cultural twinning’ which could include live streaming of music in both places, or online exchanges by teens (to learn English, for example). One idea was that we in SE14 could choose to hang a peace rock outside our own houses as a symbol of connection. Patricio is also thinking of doing something with kites, as there is so much wind in the desert and people often fly kites on our Telegraph Hill.

There are more practical ways to help: For example, there are only around 100 books in the camp library so perhaps we can provide access to more books, paper or digital. There is only schooling, provided by aid charities, for about 15-20% of children so how can we support their learning? (Graham Brown-Martin was at the meeting – and he has been helping to establish digitally-enabled schooling in another camp.) We could also think about creative ways of preventing trees from being taken from the shared spaces.

There is a big issue about whether or not the people are allowed to start any economic activity. DfID wants to prove that forming a market in the camps will make people feel better and build security. However, Jordanians are in some ways poorer than the refugees in the camp as they are not in receipt of aid, so they would be angry if this was allowed. I’m wondering if they should consider economic activity that involves no money, such as using a Local Exchange and Trading Scheme, or where all income goes towards common good projects. Has this been considered? How can creative projects start to stimulate this thinking?

One next step is to discuss how this work might also extend to support people still in Syria, refugees that are on the move, having to leave camps or not able to find shelter in camps, and refugees from other countries. In the meeting was also Augusta Quiney, who leads the artist engagement programme for Amnesty International. She explained that People on the Move is one of their next two major global campaigns so this may be a good route to feeding into a bigger initiative.

Peace Rocks!

No comments yet.